Britt Tate

Photostory by Lindy Drew / Humans of St. Louis

My husband and I decided St. Louis is where we were going to create our world and live together. We had three kids and I stayed home because they were all back-to-back-to-back. Then my daughter started at a magnet school in our neighborhood and I was very confused by the whole magnet school concept. I know now, but I didn’t understand then. One of my criticisms of St. Louis, and the educational system in general, is that you don’t know if the right decision is public or charter and you don’t know if you’re causing a problem by going a certain route. You also have your own kid and your own logistics to think about. So none of it feels great. And if a White parent with a lot of privilege feels that way, I cannot imagine being a parent of color or an immigrant parent trying to make a decision about my kid’s future, my city’s future, on top of all these other things. Nor do I know that everyone even has the bandwidth to tackle those concerns about school options.

So my daughter started school, my twins were getting ready to go to school, and I was trying to figure out a job that would work with their schedule because my husband was deploying for months at a time. Well, I’ve taught for Chicago Public Schools, I’ve done summer camps, and I have a Master’s in art, so I told myself, “I’m gonna be an art teacher.” Art is a place where kids can escape if they’re feeling unhappy, lost, or unheard. Art is where I hibernate when I’m feeling confused, frustrated, mad — all the feelings. I also had phenomenal art teachers growing up, so I thought it was my time to be that for someone else. I got fully certified and got a job with Saint Louis Public Schools [SLPS]. If all the really cool teachers go teach in the County or at private schools, what does that mean for students in the City or in public schools? I’m a product of public schools. I believe in public schools.

My schools are two miles apart in North City and it’s where I want to be and what I want to do.

Britt Tate

I started my teaching career at Carver Elementary School and eventually ended up doing a split position between two different schools. Splitting your time like that isn’t easy, but I needed to pay the bills. So I took it — and ended up winning Educator of the Year that year. The following Spring, multiple schools reached out to me with offers for full-time positions. And I was like, “Nope. I love the split now!” I love that I am in two buildings. I love that I have two art rooms. I love that I see twice as many kids. I love that I can do things that bring kids from both schools together. My schools are two miles apart in North City and it’s where I want to be and what I want to do. You know, I could take on a third school. But the fact that there are even split positions speaks to the equity issue.

It costs a college education to go to Forsyth School. And Maplewood has full-time garden teachers — teachers who just teach gardening. That’s it. That’s the kind of resources they have. Then, up here, we get art half the time and music half of the time, like visual and performing arts are not important enough to keep a full-time person. It’s a huge problem. I understand the district has to find a way to keep its head afloat. If there’s a choice between funding an extra classroom teacher or keeping a full-time art teacher, I get it. But that shouldn’t even be up for discussion in the first place.

There are days when I look at the student-teacher ratio and staffing between buildings on the South side and North side, and I’m shocked. A lot of it stems out of parent demand. If you have a school with a strong Parent Teacher Organization (PTO) and demanding parents, you get more resources. But in a school where the parents are doing the best they can, sometimes in survival mode and trying to keep their head afloat, they don’t have the time, ability, or bandwidth to say, “Wait, is my kid getting art or music every single day?”

Then the concern comes down to, “Reading and math are more important.” Districts are struggling to keep all their test scores up. I teach something that’s not on a test. It’s like, “You don’t teach something that’s testable, so you’re kind of expendable.” Now, obviously, anyone who has studied brain development and art knows that learning how to draw, color, cut, and think visually automatically helps with all the other things because they’re all interwoven. But the research is not bright and colorful and shiny. And there’s just not a lot of money. So, these are some of the first things that are cut, which is how I ended up in a split teaching position in the first place.

When people of color don’t feel heard verbally, they can be seen visually. If there was ever a time when we needed visual art, it’s now.

Britt Tate

So then let’s throw in COVID and George Floyd and all of the racial unrest. Well, what is the one thing everyone is turning to? Visuals. And that means creating posters, signs, t-shirts, and all of that stuff is being created by street artists, designers, artists of color. When people of color don’t feel heard verbally, they can be seen visually. If there was ever a time when we needed visual art, it’s now.

If you don’t have good art instruction in elementary school, you’re not going to need art teachers in middle and high school because kids aren’t going to want to take it. It is so important to have your best teachers even in elementary school. I feel like elementary schools are always given the shaft because we don’t bring in money like some of the upper schools do where they can host a basketball game and sell tickets and sell concessions. But you don’t build a house from the roof. You gotta start at the bottom.

I also advocate for early childhood education and equal elementary education. The importance of giving a three-year-old craft scissors is like that basement foundation. It doesn’t really matter if you built a house of bricks if you built it on a sinkhole. A student who starts in kindergarten might sink because you didn’t give ’em pre-K and books and fine motor skills. The earlier you get those electrons and neurons moving, the better their minds are to build.

And there is absolutely no reason that gifted schools should get full-time art, full-time music, instrumental music, dance, and all of these other things while I’m up here begging, borrowing, and stealing to get crayons and markers and having to host GoFundMe’s just to get glue. I started getting really involved in sustainability action and “upcycling” because I didn’t have art supplies. I didn’t have materials. I was having to make things out of trash — and I don’t even want to call it “trash,” because it’s not. It’s awesome. But we had to get creative because Miss Tate’s husband says we can’t spend any more of our own money on students. That’s the other thing: urban public school teachers can end up spending at least a third of our salary on supplies for our classrooms.

I’m better than I used to be. But I didn’t even wince the other day spending $150 on Amazon for school stuff. It’s quicker to just order it myself, because by the time the school or district responds to my request, or I find somebody to help pay for it, I may never get it. The other thing is, we all have a side hustle to make ends meet. I’m a baker and decorate cakes. I was a pastry chef in a previous life of mine. So I’m like, “I can order this, and then if I bake three cakes, I’ll make my money back.”

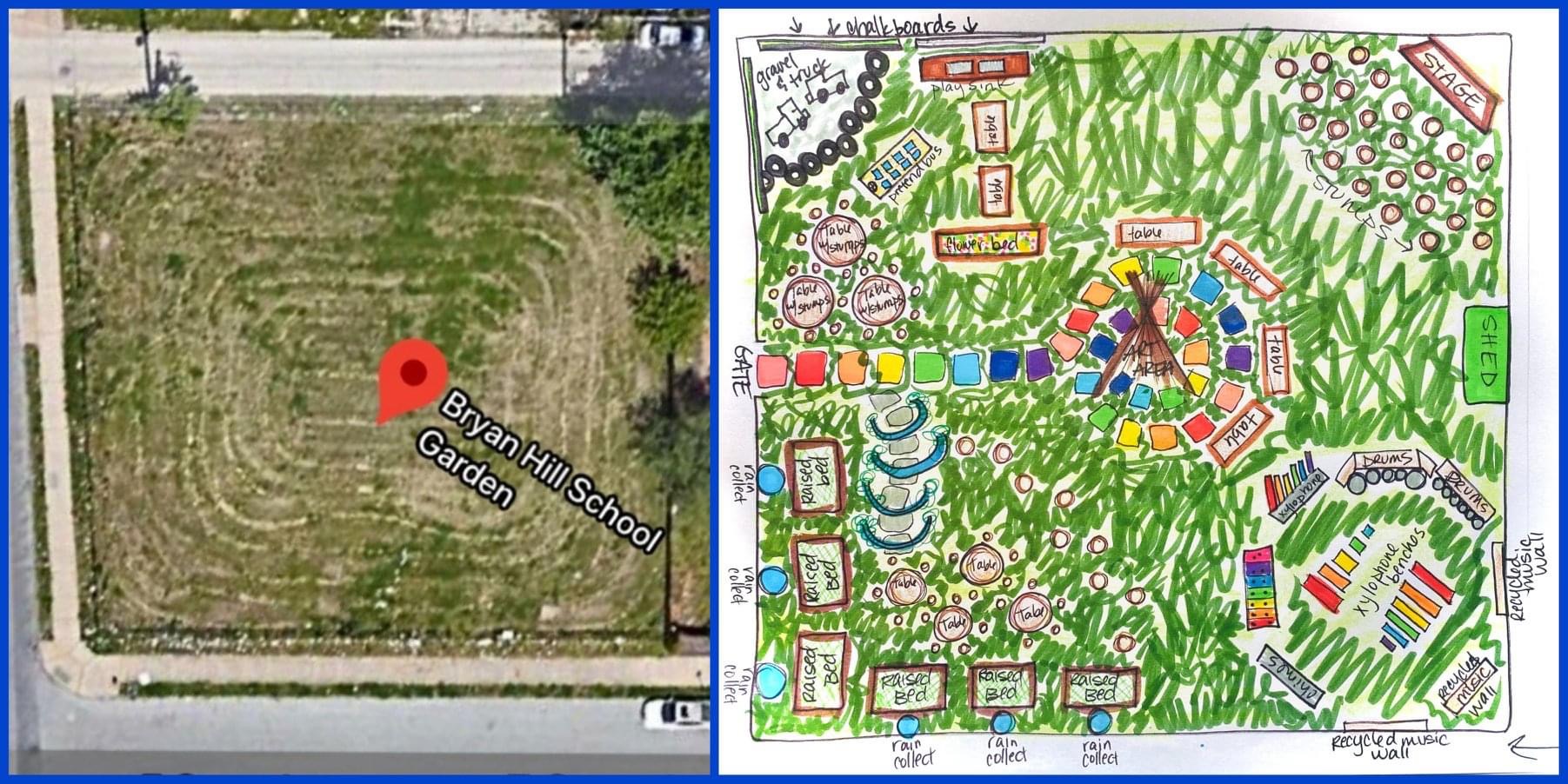

Photo courtesy of Britt Tate.

“I love teaching visual art even virtually. It’s been hilarious and we just have to sit back and laugh. I mean, I’m killin’ it. But then there was this talk of having the kids return to school. Like, “It’s fine. People can just teach outside.” Well, everyone starts posting these beautiful outdoor classrooms on social media and I’m wondering, “What district has the money for that?” We didn’t have any green space for outdoor learning. We have a blacktop, and the playground part of it was going to be closed. If you’ve ever stood on blacktop in St. Louis, you know it’s hot. So there was this empty, double lot across the street from the school and I claimed it. I just decided it was ours. It’s massive. And my idea was to make four outdoor classrooms in one lot. It was already fenced in and everything.

So in one corner, the classroom has a stage to do ELA lessons, poetry readings, and show movies. Then, in another corner, there’s a play area with gravel and tires where kids can drive toy trucks. We’re making a mud play kitchen with tables and tree stumps and flower beds. Then we’ll have an actual garden part where we’re building raised beds and a rain collection system. We’re going to plant some winter crops and go all-in for spring. Then in the fourth corner, I’m building a sound garden, music-making corner with metal trash cans I collected, plastic buckets, and xylophones made out of PVC pipe. We’re making these sound walls, which are literally just pallets with pots and pans bolted to them, and then hanging silverware so kids can bang on it.

Photo courtesy of Britt Tate.

Then, in the middle, is the art area where the dome will be. I fundraised to build a shed to lock some stuff up and keep art supplies inside. Hopefully, someone donates a lawnmower. If you know anything about North side community gardens, they tend to get ruined by bored kids. And I get it. There’s nothing to do up here. There is just nowhere to have fun. So I cannot blame kids for walking around, kicking stuff, and just destroying things. But I thought, if I can set it up so the entire community can come over and hang out and pound on trash cans and record music with their phones, and rap and do whatever they want to do, they can get on the stage and do their thing. They’ll protect it. They’ll be interested, and they’ll be invested.

I have done all of this since the middle of October. I dreamt it up the week that the admin had the work meeting to discuss returning to school. All of a sudden I got the idea to make this. I reached out to Tosha X Phonix, who is a food justice badass, to ask, “Can you help me?” So she and I met. Our sons were hanging out in our cars, and she and I were tailgating with our phones, showing each other Pinterest boards, like, “Do you think we can make this?” She’s all about the food and the garden aspects, and I’m all about the art and the making and building. I put my ideas to paper, posted it on Facebook, and let people know the list of things I needed. It just started pouring in. Things started showing up at my house. I hit up the Facebook Marketplace for stuff. I started giving people the garden’s address and told them, “If you’ve got wood, dump it at the site.”

There were a lot of issues at first, because all of a sudden, every weekend, this car full of White people showed up and started working. And there was a lot of mistrust, like, “Wait a minute. Who are these White people and why are they all in this lot?” Then we put the signs up that said, “Community Garden for the School — Coming Soon.” And then people started stopping. A City bus driver stopped the other day when I dropped off 15 trees I got from Forest Relief. She asked, “What organization is doing this?” And I was like, “Oh, we’re building a community garden with the school across the street.” And she was like, “Oh, okay. Nevermind. You’re fine!”

Photo courtesy of Britt Tate.

So now I named it and have been using the hashtags #BryanHillSoundgarden, #BryanHillOutdoorMakerspace, and #BeautificationWithoutGentrification because I think that’s important. I’m not trying to call this lot mine or make it just for the school. I’m not gonna put a gate on it. I’m not going to lock it. Because this needs to be something that everybody in College Hill can wander into, even just to sit down. We’ve been building these cool little stools out of tires where you can sit and chill. I drilled holes and wove rock climbing rope through, and it’s got this little bounce to it. I mean, are there people who are potentially going to be having sex on the stage? Yes, that’s going to happen. It happens everywhere. It is what it is. But 95% of the time, that’s not what’s going to be happening there.

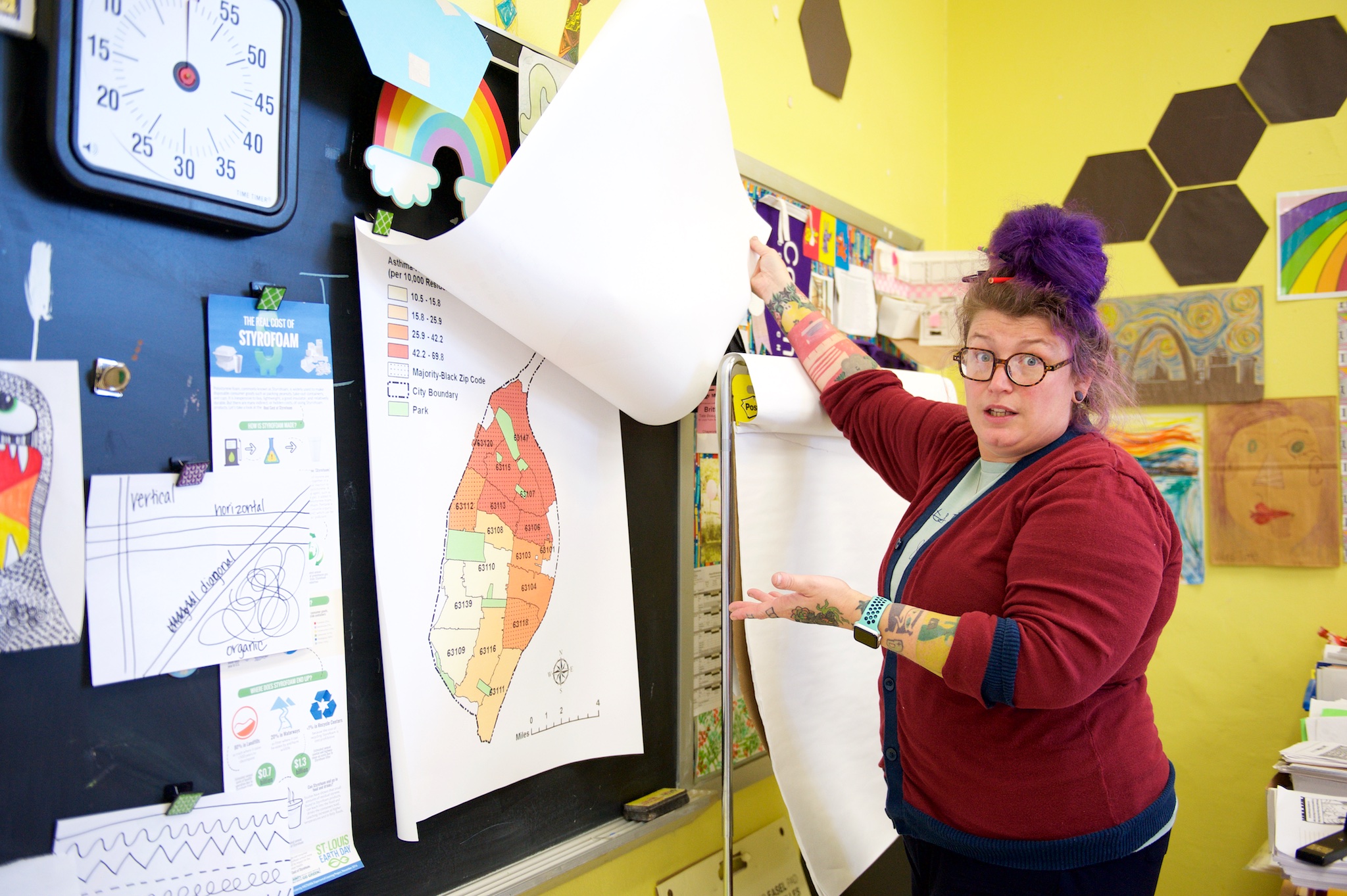

As a White teacher on the North side, what does inequity look like to you? What do you talk about amongst the staff? What do you hear from the children, from their voices and eyes and ears?

I also teach at Columbia Elementary, where they started to build a North side gifted program. We have a partnership with the two gifted schools on the South side, which are very full and at capacity and heavily White. So when COVID started and through the Fall, we opened instructional care centers. Everyone was learning from home and teaching from home, but they opened up select schools to host kids whose parents had no option and needed childcare. Well, the kids at Columbia got to go to Mallinckrodt as the hub school for their instructional care center. And those kids immediately picked up on how that school was entirely different from where they normally go to school.

Usually, kids don’t realize the inequity unless they’ve attended school at other schools. Unless they’ve gone to school on the South side or went to school South of Delmar, they don’t really know. They hear, but they don’t see how different it is until maybe they go to summer school somewhere.

Britt Tate

Usually, kids don’t realize the inequity unless they’ve attended school at other schools. Unless they’ve gone to school on the South side or went to school South of Delmar, they don’t really know. They hear, but they don’t see how different it is until maybe they go to summer school somewhere. Well, all of a sudden, I remember talking to this 5th grader from Columbia. It was the end of the day, and he was like, “Yo, Miss Tate. This school is hella nice. They got everything. They got a real nice garden. Their gym is real nice.” He immediately picked up on the fact that the building was taken care of better and everything was nicer. He was like, “Even the bathrooms are nice.”

See, that’s a problem. And that’s the look of the place with a skeletal number of people in it. That’s not even what the place looks like full of all the hustle and bustle. And I knew because that’s how I felt the first time I realized the difference. My daughter did summer school one summer at Kennard Elementary. And I remember walking in the door, like, “Hold on. We got one working stall at my school. We got cinder block walls. And I can’t even get a new bulletin board, but y’all got banners. This is some shit.” A lot of it is because funding is linked to test scores and their test scores are higher. Some of it is credited to a school’s PTO. Some of it is just linked to name recognition, so they just get everything, or it at least feels that way.

I mean, the day we beat them in the science fair, oh God it felt good. We worked so hard on that science fair project, and we literally dropped it off the day we shut down for the pandemic and never came back to school. So I got a phone call from downtown and she said, “I just want to tell you that your science fair project was phenomenal. I cannot believe you’re an art teacher because the science behind this was incredible.” And she added, “I LOVE that you are from a neighborhood school on the Northside. I love that some little neighborhood school in College Hill beat out the rest.” When people who work in the district know — that’s how you know it’s bad.

What do we have to do to get some notoriety? The South side is known for being smart and winning and White. The North side is known for deterioration and low attendance, and everyone assumes we’re all crappy teachers because our test scores are bad so it must be our fault. Arguably, we’re some of the best teachers in the district because we are also social workers, counselors, and fundraisers. We’re doing five jobs. Normally, we have a part-time nurse. Our social worker’s here for one and a third day a week, whatever that means. We have a full-time counselor, but it’s only because our principal advocated and got it. The amount of work our principals have to do to advocate for just the bare minimum is crazy.

Even with COVID, here’s what’s messed up. They polled all the parents to find out who wanted to come back and who needed childcare. And you know where the bulk of the instructional care centers were? On the South side, because it was White parents who wanted their kids at school. It wasn’t the poor Black parents. Like, that’s everyone’s excuse: “Oh, we all need to be in the buildings for those poor kids up North who don’t have food and stuff.” No, that’s not who wants to be in the buildings in school.

The money goes where the White kids are. And when that happens, it just leaves everyone else in the dust. The test scores are better because the technology’s better, the resources are better, the classroom ratio numbers are better. We had a class last year that had 34 fourth-graders in it with a brand new, first-year teacher. And we were told we wouldn’t get another teacher until there were 35 kids because they needed to be able to justify it to say there was a class of 17 and a class of 18.

So that new teacher had two choices. She had to either pray for another kid and hope the district found another teacher or just continue to teach 34 kids. And by the way, she knocked her first year of teaching out of the park! She was the perfect teacher for that group of kids. We had a similar situation in kindergarten. We had 35 kindergarteners in one class, and all year long we were being told, “We’re find you another teacher.” That teacher never showed up. That’s the other problem. There are all these vacancies in our district because we’re underpaid. Because we’re paid so little and the job is so demanding, teachers don’t stay.

I don’t want to say our kids of color fall through the cracks or that they’re disenfranchised, but there are definitely days when they’re just going through the motions. One of the things I notice is that we struggle to support parents because a lot of them are fresh out of one of several districts in the area, and they didn’t have a good academic experience. So by the time they put their own kids in school, they are disinterested in being involved. It’s like, “Man, I remember being a kid and it was terrible. My teachers didn’t like me. Nobody gave a shit, it was boring, and I never saw myself represented.” Grandparents and parents got labeled Special Ed, so there are generations of kids who have been mislabeled.

Then when you do have a kid who really could use some services, their parents are like, “Uh-uh, you are not going to label my child.” Or, a ton of parents end up medicating their children. Education is linked to Medicaid. And if a kid is having problems in school, a doctor’s solution is to medicate with Ritalin to just chill kids out instead of recommending behavioral therapies or something. Kids are antsy. Like, hello! They’re just people. They’re wiggly little goofballs. I live with a seven-year-old boy. You don’t know when it’s coming.

These disparities you're describing between schools on the North side and schools on the South side are not new, and they're not secret. Why do you think we're still dealing with these issues?

White people act like they want to be “woke” and like they’re ready to fight and advocate. But they’re not willing to send their kids to school up here. I get in fights all the time on three or four different mom Facebook groups. I actually stopped with a lot of them because I can’t with these moms. They’ll share, “Well, at my kid’s school, the classroom sizes are so full” and dah, dah, dah, dah, dah. And I’m like, “Guess what? Your kid can come up to Columbia Elementary, because our gifted teachers have the same curriculum, the same credentials, and we’re providing the same programming. You’re more than welcome to put your kids on a bus and they can come up to the North side to get the same gifted education.” But, they’re not going to.

Everybody can sit in these Zooms and say, “I agree. Public education shouldn’t be linked to property tax.” Yeah, but also when it’s time for your kid to go to middle school, are you still going to be living in the City?

Britt Tate

We have one White kid in one of my schools. And I was surprised he came back this year because they typically come for like a year or two and then families are like, “Nope. We tried. We’re going back to the South side.” So until White people are willing to put their kids and money and themselves where their mouth is, it’s not going to become equal. Everybody can sit in these Zooms and say, “I agree. Public education shouldn’t be linked to property tax.” Yeah, but also when it’s time for your kid to go to middle school, are you still going to be living in the City?

You can find a good elementary school in the City, but it’s hard to find a good middle school. Middle school is like the armpit of education. That’s when White flight really takes off. All of a sudden parents are like, “Well, our kids need to go to a good middle school because they need to go to a good high school.” And they don’t want to pay for private school because college isn’t going to be far away. The other problem is then you have Black families who may feel disenfranchised by SLPS. So they try Riverview Gardens and Ferguson-Florissant. And all of these districts have the same problem. So they bounce around to try the County because maybe that’s better than the City. Spoiler — it’s not. Not North County. You can cross that line, but the same thing is on the other side.

School segregation started a long time ago. This is not something that started with COVID or five or ten years ago with the Delmar Divide. This shit’s all by design. I’ve worked in three elementary schools: one where the teachers were predominantly White, another where it was 50/50 White and Black teachers, and at Bryan Hill Elementary where my first-year, I was the only White teacher and all the other teachers were teachers of color. There were really big differences in the teacher makeup for schools that serve BIPOC communities.

Knowing what I’ve learned in the last few years, I worry we were doing a disservice to kids at my first school with all those inexperienced teachers. They were not prepared. They didn’t know how to build relationships. There were trust issues left and right. And we were really ruining the educational experience for a lot of those kids, which became evident as attendance and enrollment dropped. We all know we can do better as educators.

The sense of community at the school I’m at right this minute, with a predominantly African-American teaching staff and a couple of White teachers, is a very different vibe. We are a community. We are a family. If you have a problem with your electricity, we’re gonna find someone in this building to help you out. And if you need food, we’re going to find someone. And if you need Christmas gifts, we’re going to find something. The school is a pillar of the community here, to the point where when I put the signs on the garden saying “Future site of Bryan Hill Community Garden,” all of a sudden, all of the damage being done to the site stopped because it’s part of the school.

We make it work. We find a way. And we find a way to make it fun to the point where kids come back when they go to middle school and are like, “We were spoiled in elementary school.” Even middle school teachers tell us, “Y’all spoiled these kids.” First of all, they’re kids. How do you not? Second of all, there’s something that happens when you go to middle school and everyone just decides you’re grown. And that’s not fair.

Photo courtesy of Britt Tate.

It’s hard as a parent to figure out where to send your kid to school. There are a lot of parents who are like, “My kid won’t go there because I went there and it’s terrible.” And then other parents are like, “I need them all in the same building. I’m not going to have one kid here and one there.” I did the same thing. My daughter got into a private school, and I moved the twins. I had initially split them up and tried a couple of schools. But, nope. I needed them all in one place. So, it’s really tricky. My situation is interesting because I’m the mother of three and my kids started at SLPS. I started at SLPS. And then I pulled my kids out of SLPS. My kids go to City Academy, which is a private, independent school at Kingshighway and I-70. They are 90% to 95% Black. And some parents are like, “Why am I going to spend money on a private school in north city?”

I picked that school with a lot of intentionality. We were accepted there, and I loved everything about the way they were teaching. They do this huge emphasis on character. If you get the academics, that’s great. But so much of it is about how to be a person in society and tackle the good, the bad, and the ugly. Whereas in public schools, we’re so bogged down with the academics that we’re missing all of the character and the human aspect of learning. And that’s where art is really great, because I’m allowed to teach the human aspect and art at the same time.

I also picked a school that was gonna look like public school, because I wasn’t going to send my kids to some gifted White bubble because that’s not the world they’re gonna live and grow up in. At the end of the day, I’m their only advocate right now. I am a St. Louis resident. I am a teacher in this district. And I’m a mother in this City. I am a North side, public school teacher who pays property tax in one of the most expensive neighborhoods in this City. I send my kids to private school.

I want people to know that, yes, the Delmar Divide is real, but there is some amazing stuff going on up here. There are some absolutely phenomenal people advocating for this North side. And there are some beautiful humans just trying to get by and do what they can. There are a lot of stereotypes that are so ignorant about the North side. And, granted, there’s some stuff that’s true. Even working in the garden, we’ll hear gunshots. My kids know to drop. Do I come up here and work in the garden after dark? No, but I also wouldn’t do it on the South side either.

Leaving the City is not going to fix anything. Putting your kids in magnet schools isn’t going to fix it. Putting your kids in charter schools isn’t going to fix it. The only thing that’s going to fix it is advocating for legislative change. We need to elect leaders who look like the people in our City. We need to also hold the people who are in charge to a higher standard. I would not want to be the superintendent of SLPS. But he wanted the job, he’s got the job, and he’s gonna need to do the job.

What does that ultimately mean for the kids?

When kids see grownups advocating for them, it gives them a sense of worth and hope that the future isn’t going to just be the same thing it is right now. When they see a city rally behind them and when they see the grownups around them appreciating them, they’re like, “Oh, okay. This can go somewhere.” I’m not someone who advocates for every kid to go to college. I don’t really believe in that system of you either go to college or you’re a loser. That’s not true. There’s a lot of area in between. But I do believe in every kid going as hard and as far as they can and finding something that they’re good at.

I own two very expensive art degrees. I use them, but I’m also really glad I did not go to college to become a teacher because the education of educators is super flawed. That system alone also feeds into this inequity because we are not teaching teachers how to be anti-biased and anti-racist. We are not preparing teachers to teach anyone except for White kids. We live in this world that’s so caught up in benchmarks and standards and rubrics. Why are we making education so difficult?

Britt Tate

Bryan Hill Elementary School and Columbia Elementary Academy School Art Teacher