Structural Inequity

EDUCATION QUALITY & ENVIRONMENT

Bottom Line Up Front

Racialized Differences in Funding Contribute to Differences in Educational Environment

Download This Section

Download the Funding section of the report

Download Entire Report

Download the entire report

Background (in Brief): The Missouri School Improvement Program (MSIP) is the state’s accountability system for reviewing and accrediting public school districts. It forms the foundation of how we determine whether a school district is “accredited.” MSIP 6, the current system, makes important improvements over MSIP 5 by emphasizing measures of school culture and climate, data transparency and utilization, and equity and access to quality education. However, state standards take little consideration of important factors that affect a school’s ability to educate its students like poverty, funding, and student mobility. This shortsightedness is a symptom of state level education structures that are not doing enough to ensure the quality of education received by low-income Black students.

Findings Snapshot:

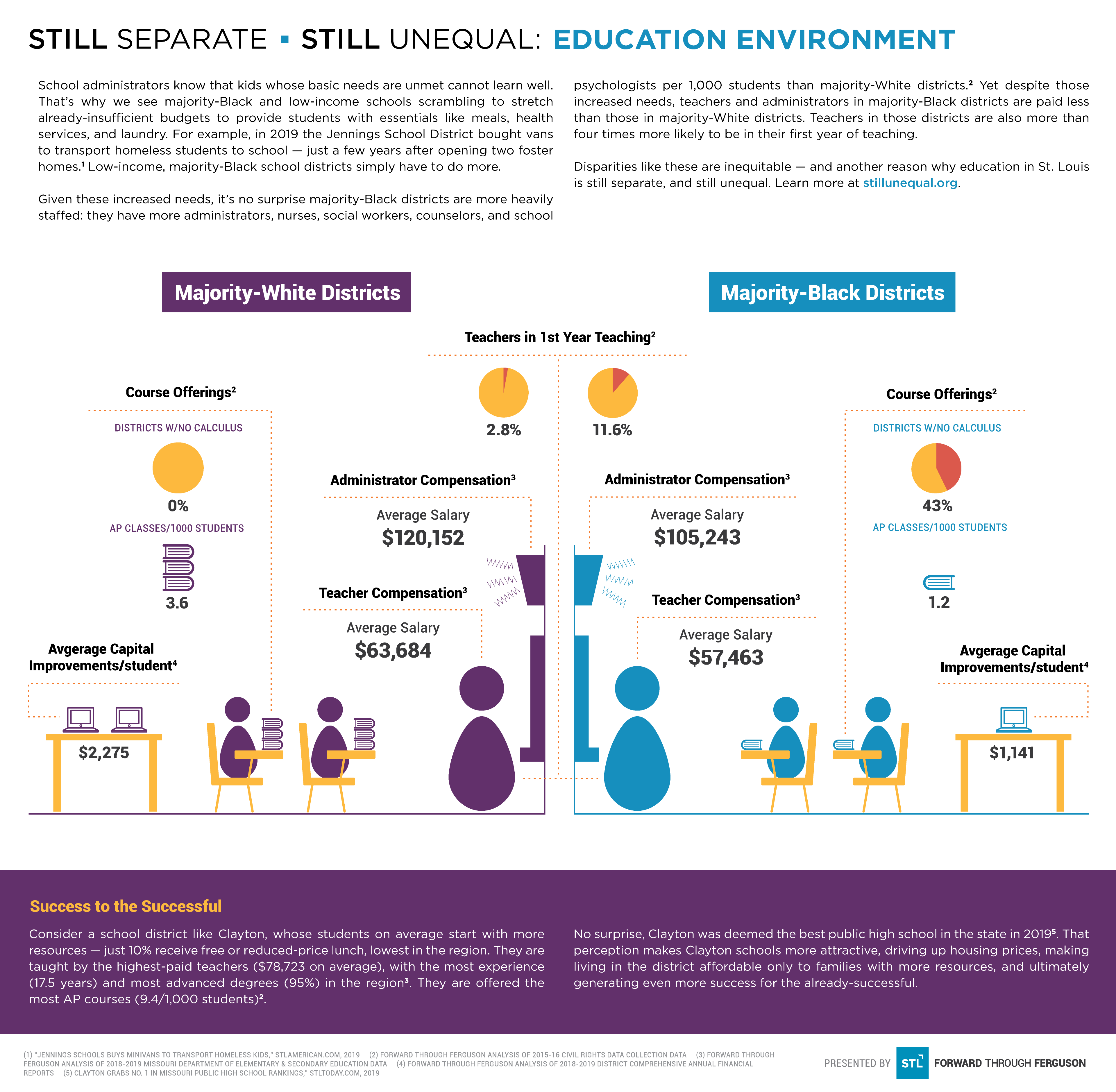

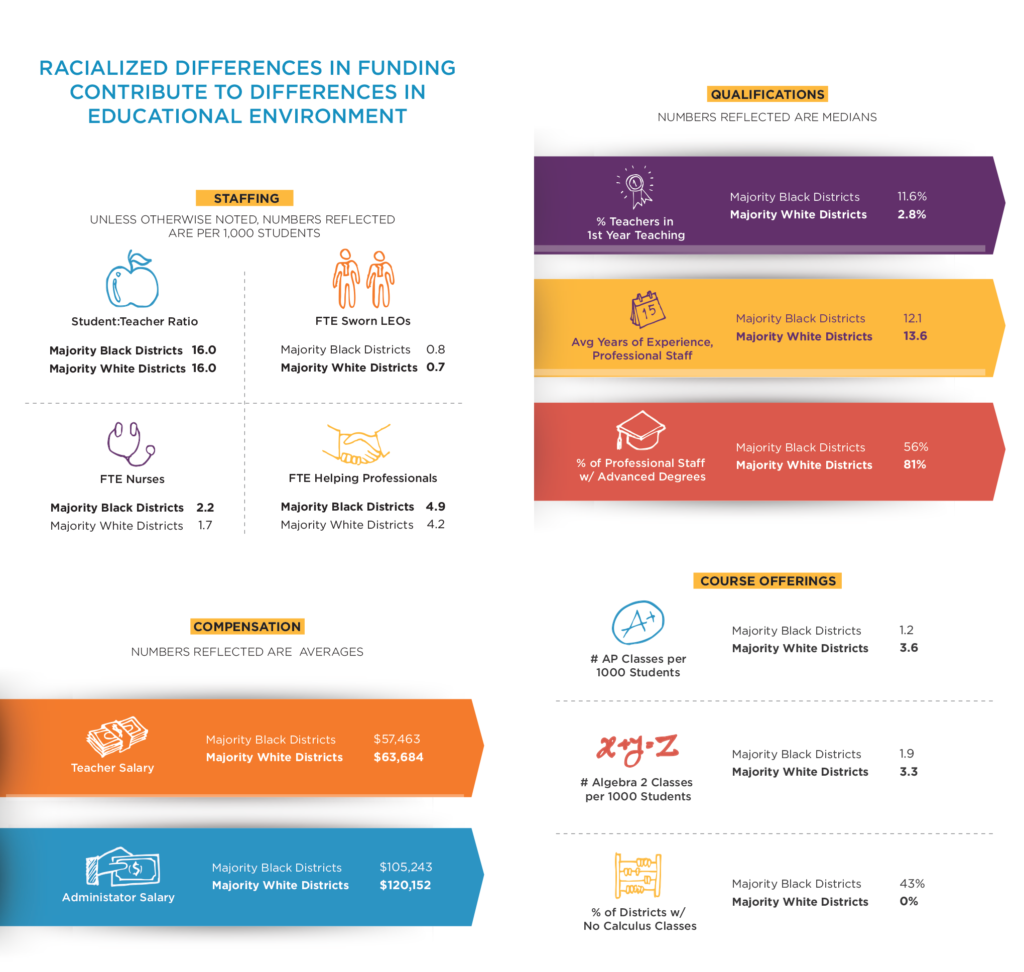

- For 3 of the 4 measures we looked at, majority Black districts in the St. Louis region were more heavily staffed than majority White districts. This makes sense, since these districts tend to have students with greater needs.

- However, teachers at majority Black districts are paid, on average, 10% or $6,221 less. Administrators are paid 13% or $14,909 less. The highest paid teachers are in Clayton, where they get paid $78,723 on average. This is 61% or $30,000 more than the average salary of a teacher in SLPS—the largest educator of Black children in the region.

- In some ways, the pay disparities are understandable: administrators and teachers at majority White districts tend to have more years of experience and more advanced degrees. Teachers in majority Black districts are 4.7x more likely to be in their first year of teaching.

- This likely contributes to the less rigorous course offerings at majority Black school districts. Majority White districts offer 3x as many AP courses per 1,000 students as majority Black districts. 43% of majority Black districts don’t offer calculus. Not a single majority White district fails to offer this course. Over 1 in 4 Black students in our region attend a school district that either doesn’t offer Calculus or any AP courses. Less than 1% of White students attend such a school—and the White students who do lack access to these courses are all enrolled in a majority Black district.

Selected Next Steps

(*** indicates a near-term area of focus for FTF)

***Grow broad community understanding of the structural inequities in the St. Louis regional education landscape including the state standards program (MSIP).

Grow next-level education partnerships to organize and strategize on equity-centered advocacy to redesign education funding and accountability mechanisms, including the state standards programs.

In partnership with diverse stakeholders, identify statewide advocacy targets. Potential options include improving state standards program (MSIP) by further applying an equity lens. [ed environment]

“We’re not looking enough at the impact race is having in school systems. Race-based incidents are going to continue to happen in schools, particularly in predominantly White institutions. How are we supporting our students when this occurs? This is part of the reason I worry about underrepresented students, regardless of if they are in an urban, rural, or suburban school.”

Click here to read the full conversation between Dr. Nicole Evans and Dr. Howard Fields.

Background

School districts with more money can buy their students a better education. This is actually a fairly contentious statement. There is a decades-long debate over whether what matters in school funding is how you spend the money or how much you spend. In favor of the former idea is research that finds that there is no link between funding and academic achievement. Applying a racial lens, other studies have found that, even in wealthy school districts, Black students tend to under-perform. In favor of the power of funding to improve educational outcomes are studies that find that states that underwent education funding reform with an eye on equity and adequacy saw improvements in the racial achievement gap. Research has also found that steadily increasing school spending leads to better long-term outcomes for poor students, including a decrease in the likelihood of being poor as adults, an increase in the odds of graduating, and an increase in earnings as an adult. In short, as one article summarizes, “spending more in troubled schools won’t automatically lead to better student outcomes. But, when the dollars are spent wisely and consistently, research suggests, they can have a profound effect in the classroom.” Extra dollars translate to higher paid teachers, newer and safer buildings, more course offerings, additional extracurricular options, and better technology, all of which can contribute to better outcomes.

It can be difficult to get a line of sight between the countless ways a district can spend money and the actual improvement of the quality of education they provide to their students. But we do have a few standardized ways of measuring education quality. Chief among them is the Missouri state education standards system.

MSIP is the State’s Education Accountability System

The Missouri School Improvement Program (MSIP) is the state’s accountability system for reviewing and accrediting public school districts. While there are federal standards requirements for funding through the Every Student Succeeds Act, Missouri’s plans for meeting those requirements are minimal because of the state’s investment in the MSIP system. MSIP has been in place since 1990 and, since then, has gone through six iterations. The current standards, MSIP 6, were approved in February of 2020 and will go into effect in 2022.

MSIP 6 is made up of indicators in six domains: Leadership, Effective Teaching and Learning, Collaborative Climate and Culture, Data-based Decision Making, Alignment of Curriculum and Assessments to Standards, and Equity and Access. By comparison, the MSIP 5 domains were Academic Achievement, Subgroup Achievement, High School Readiness or College and Career Readiness, Attendance Rate, and Graduation Rate. The MSIP 6 standards are new enough that there isn’t much documented critique from school districts, advocacy organizations, professional associations, and the like to share opinions on how they compare to MSIP 5 standards. However, early analysis suggests that MSIP 6 makes important improvements over MSIP 5 by emphasizing measures of school culture and climate, data transparency and utilization, and equity and access to quality education. Much remains to be seen as the specifics of the new standards are made public in the coming years.

MO Education Standards Are Improving But Are Still Fundamentally Flawed

However, Missouri’s approach to state standards for education seem divorced from reality in some key ways. For example, they take little consideration of important factors that affect a school’s ability to educate its students like poverty, funding, and student mobility.

Essentially, the current standards ask low-income districts to perform on the same level as middle-income and wealthy districts when they 1) have less funding per student and 2) have more students that are more expensive to educate. We aren’t suggesting that low-income, majority Black school districts should be given a lower set of standards to meet. In fact, there’s evidence to suggest that standards have been engineered to allow school districts that are failing in fundamental ways to still receive an overall passing grade, which is deeply problematic. Rather, we are suggesting that the lack of an equity lens on state standards is symptomatic of state-level education structures that are not doing enough to ensure the quality of education received by low-income Black students.

Performance on MSIP is the Primary Way the State Determines Accreditation Status

It’s essential that we get these standards right, because they form the foundation of how we determine whether a school district is “accredited,” or performing adequately and whether our students are getting the high quality education they deserve. School districts receive their accreditation status each year after an Annual Performance Report that measures and shares their achievement on the MSIP standards. The State Board of Education monitors districts that are provisionally accredited. If a district remains provisionally accredited for long enough, or if something drastically changes for the worse, it risks becoming unaccredited, which allows the state to step in and exercise stricter control over the district—for example, by disbanding the district’s school board and establishing a state-supervised school board.

Loss of accreditation also triggers a provision of the 1993 Outstanding Schools Act that allows students of unaccredited schools to transfer to an accredited school at the expense of their home district. This right was affirmed by the state Supreme Court in the 2013 Breitenfield vs. School District of Clayton case filed after SLPS lost its accreditation in 2007. Between 2013 and 2017, thousands of Black students from Riverview Gardens and Normandy school districts, which lost accreditation in 2007 and 2012 respectively, used this mechanism to leave those districts in favor of fully accredited districts.

There’s a World of Difference in the Educational Environments our Students Face

The educational environments those students encountered at their transfer schools were, in many ways, wildly different from what they left. An article from the time paints an astonishing picture of what school in Normandy was like when it lost accreditation. It begins:

“Cameron Hensley is an honors student at Normandy High School with plans for college. But this year his school quit offering honors courses. His physics teacher hasn’t planned a lesson since January. His AP English class is taught by an instructor not certified to teach it.”

And continues,

“Hensley, 18, began his senior year to find his favorite teachers gone. Electives such as business classes and personal finance were no longer offered…He has written no papers or essays since fall, he said, aside from scholarship applications. He started reading a novel that the class never finished. Partly because of a lack of electives, he ended up taking fashion design first semester. He has no books to take home. He’s rarely assigned homework.”

Hensley had the option to transfer but chose to stay and correct what he, at the time, thought was an unfair misperception of his school district. Transferring would have likely led him to Francis Howell, a well-resourced district catering to an almost entirely White student population.

What We Looked At

Note: Each of the following indicators were examined by district as well as for majority White and majority Black districts. These classifications were made using 2018-2019 enrollment data from the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (MO DESE).

What We Found

As we established in Section 5, St. Louis majority White districts tend to receive more funding, especially from the local level, which is generally more stable and less restrictive than state and federal funding. So, what do those additional dollars buy majority White districts?

Majority Black school districts are more heavily staffed

Not necessarily more staff. It may come as a surprise, but, majority Black districts in the St. Louis region were more heavily staffed than majority White districts in terms of three of the four indicators we looked at. While majority White schools had more teachers, majority Black districts had more administrators, nurses, social workers, counselors, and school psychologists per 1,000 students than majority White districts.

This makes a certain amount of sense: students at majority Black students, as we discussed earlier, tend to have greater needs. They are more likely to live in food insecure households, to have less access to healthcare, and to have experienced (and/or be experiencing) trauma. School administrators know that kids with unmet basic needs cannot learn well—they also know that absenteeism due to unmet needs translates to less funding for the district. Meeting those needs takes resources. So we see schools scrambling to stretch already-insufficient budgets to provide students with the essentials.

In 2019, Jennings bought vans from Enterprise Rent-A-Car to transport homeless students to school. A few years earlier they opened two foster homes for homeless students. Some SLPS schools have washing machines for students to use. Several schools in the area have school-based health centers that provide medical, behavioral health, and social services. Low income, majority Black school districts simply have to do more for their students.

But educators at majority Black districts are paid less

While some staffing ratios are higher at majority Black school districts in St. Louis, the same cannot be said for compensation. Teachers and administrators (and, it stands to reason, the staff, though we do not have data on this) are paid less on average than their counterparts at majority White school districts. Teachers at majority White districts are paid, on average, 10% or $6,221 more. Administrators are paid 13%, or $14,909, more. The highest paid teachers are in Clayton, where they get paid $78,723 on average. This is 61% or $30,000 more than the average salary of a teacher in SLPS—the largest educator of Black children in the region. Valley Park, a small majority White district of less than 1,000 students, pays its administrators $144,651 on average—nearly $50,000, or 53%, more than the average administrator pay of $94,823 at SLPS.

Educators at majority Black districts have fewer traditional credentials

In some ways, the pay disparities are understandable: administrators and teachers at majority White districts are, on the whole, more qualified in the most traditionally quantifiable ways. Professional staff have, on average, 1.5 additional years of experience and are 38% more likely to have an advanced degree. Teachers in majority Black districts were 4.7x more likely to be in their first year of teaching in 2015, the most recent data we have.

There’s nothing wrong with being a new teacher. We aren’t saying new teachers don’t work just as hard or care just as much as veteran educators. We’re saying that teaching is incredibly difficult. As a result, nearly half of new teachers quit within their first five years. Amidst a national shortage for qualified teachers, this is both cause and effect of underqualified teachers in under-supported classroom settings. If departures happen in the middle of the school year, they are associated with a loss of 32-72 days of instructional time. In four majority White districts (Parkway, Clayton, Kirkwood, and Rockwood), less than 1 percent of teachers are in their first year of teaching. By contrast, over 40% of the teachers in Normandy Schools Collaborative were in their first year in 2015-16.

Fewer qualified teachers means fewer advanced courses

A less qualified teaching staff has implications for the classes a district is able to offer. One of the central charges of our public education system is to prepare students for success in life, and, as discussed, a primary vehicle for that success is a college degree. But many of our Black students attend schools that structurally do not provide them with the course options needed to get into and succeed in college.

For example, majority White districts offer 3.0x as many advanced placement (AP) classes as majority Black districts. They also offer more Algebra II and Calculus courses. In fact, 43% of majority Black districts didn’t offer Calculus in 2015, the most recent data we have for this indicator. Not a single majority White district fails to offer this course. About 28% of all the Black students in our region attend a school district that either doesn’t offer Calculus or any AP courses. Less than 1% of White students attend such a school district (and those who do are enrolled in a majority Black district).

Setting aside the countless conversations we’ve heard and read about achievement rates in those courses, we are drawn to a more fundamental question:

What are we telling those one in four Black students about our expectations for them when we don’t even offer them the opportunity to take advanced courses?

Resources for learning more about these topics

A Senior Year Mostly Lost for a Normandy Honor Student, 2015. By Elisa Crouch.

Understanding Teacher Shortages: 2018 Update, 2018. By the Learning Policy Institute.

Teacher Quality Gaps in U.S. Public Schools: Trends, Sources, and Implications, 2019. By Dan Goldhaber, Vanessa Quince, and Roddy Theobald.