Structural Inequity

PROPERTY TAXES

Bottom Line Up Front

Funding Education Through Property Taxes is Inequitable

Download This Section

Download the Property Taxes section of the report

Download Entire Report

Download the entire report

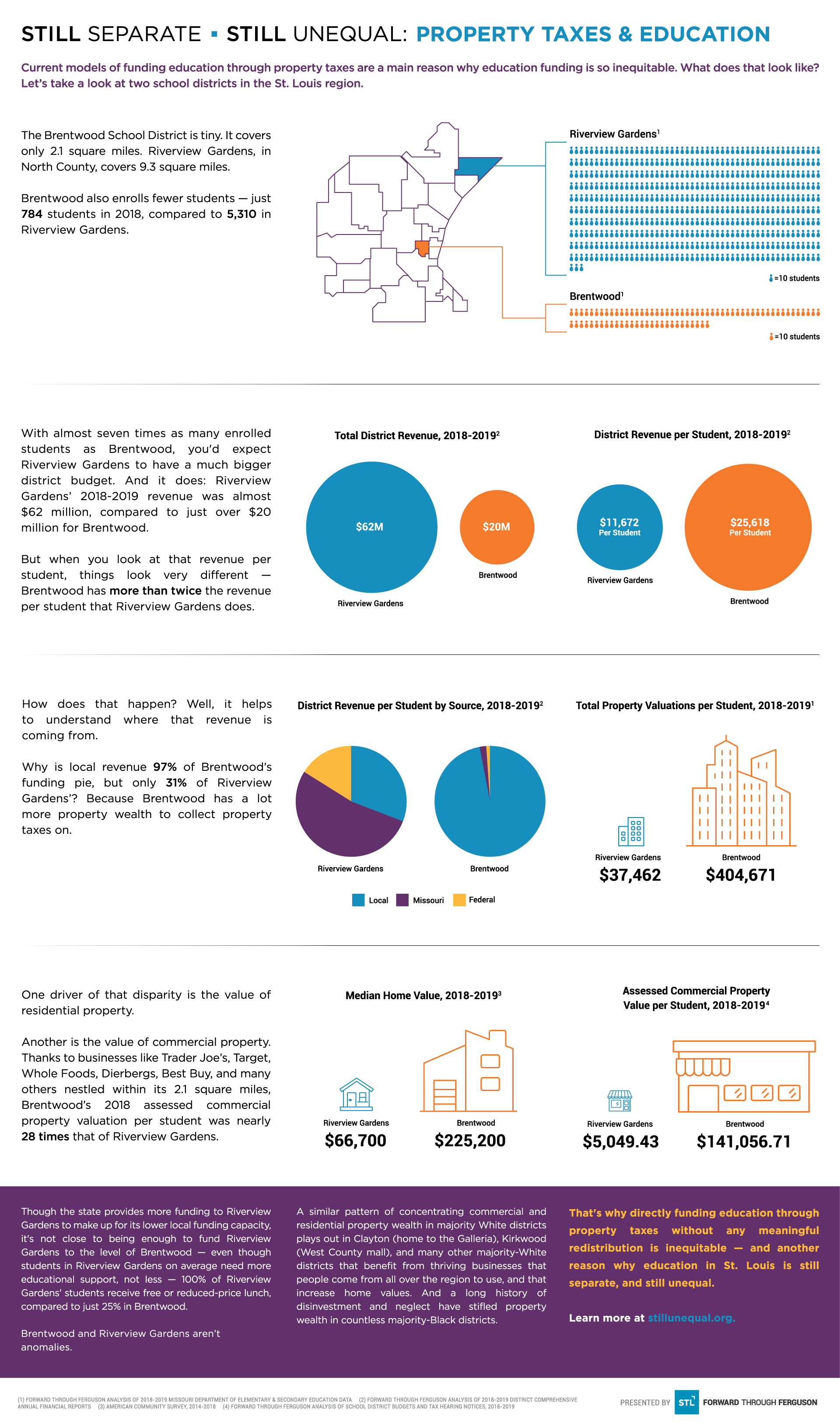

Background (in Brief): Property taxes are the biggest wedge of the local funding pie. The bulk of property value in a district tends to come from residential properties, though commercial property can be a powerful—and under-discussed—contributor to education coffers. School districts set their tax rates each October, but if they want to set it above a certain ceiling, they must get voter approval.

Findings Snapshot:

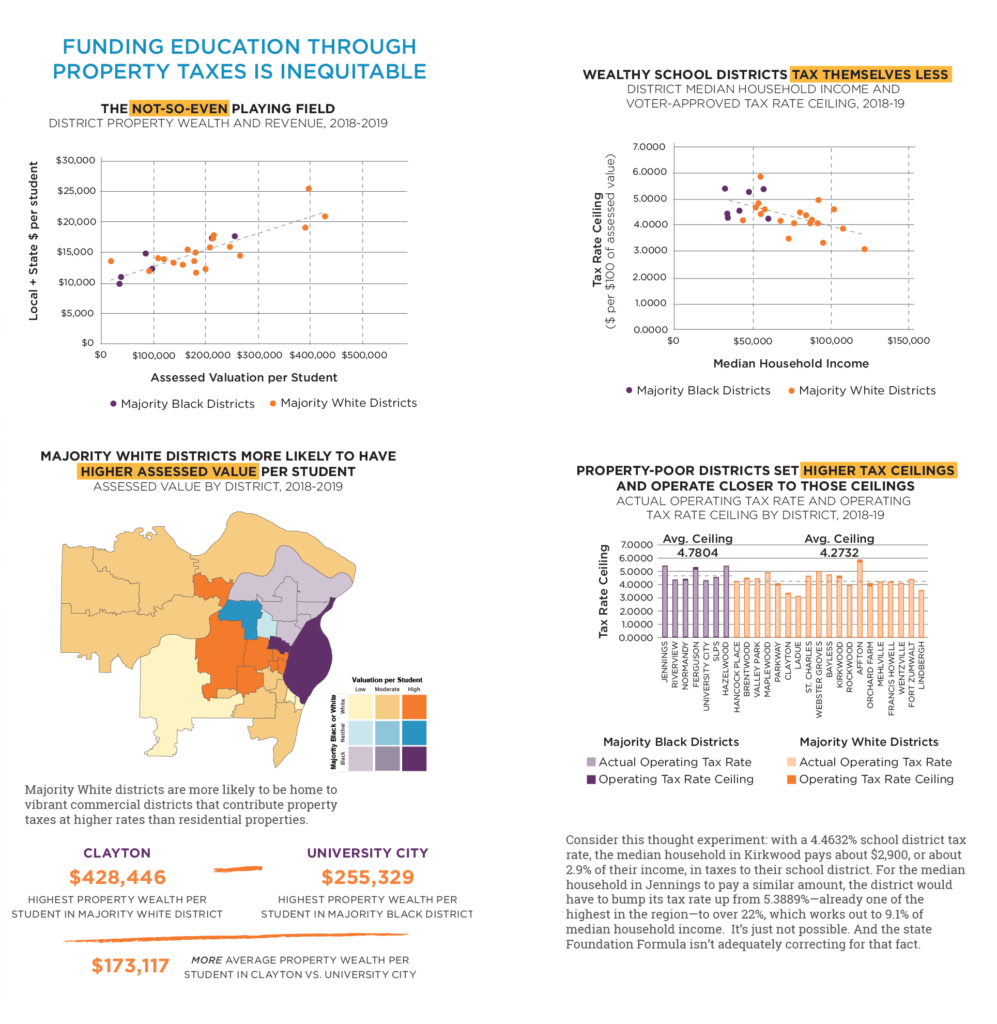

- The Foundation Formula is supposed to fill the gaps left by uneven local funding. But the strong, positive relationship between the property wealth in a district and the local and state revenue it receives suggests the Formula is not working.

- This is partly because of the vast difference in property wealth in our region: the median assessed value of the property in majority White districts is $181,899/student compared to $97,751 in majority Black districts.

- To make up for their lower property values, majority Black districts tend to have higher tax levy ceilings ($4.7804 per $100 of assessed value on average vs. $4.2732)—meaning their residents voted to tax themselves more heavily, despite having about half the income (median of $41,107 vs. $79,729).

- But even with higher taxes, majority Black districts don’t come close to raising what White wealthy districts can raise at the local level.

Selected Next Steps

(*** indicates a near-term area of focus for FTF)

***Grow broad community understanding of the structural inequities in the St. Louis regional education landscape including the practice of directly infusing property taxes into school districts without redistribution and awareness of alternative models.

Grow next-level education partnerships to organize and strategize on equity-centered advocacy to redesign education funding and accountability mechanisms, including local allocation of property taxes.

In partnership with diverse stakeholders, identify statewide advocacy targets. Potential options include redistributing local funds before infusing them into school districts drawing from existing, successful models in other regions, including pooling property taxes by county.

“We are condemning schools to being under-resourced and of lesser quality because we’re tying it to property values of neighborhoods or of a place. And then the property values are historically tied to where Black people are or are not. So we’re creating this terrible cycle that says Black children are undeserving of high-quality, high-resourced educational experiences and supporting that stance with the continued devaluation of properties in Black neighborhoods.”

Click here to read the full conversation between Dara Eskridge and Colin Gordon.

Background

In the previous section, we learned how overall funding for education varies widely across the 28 districts in St. Louis City and St. Louis County, despite a state funding model that is intended to even things out. We hinted in that section at what we will more fully discuss now: that variability is driven by funding variations at the local level because of huge variability, in turn, in the value of the property contained within districts.

To back up a step, though: “local” sources of funding actually refer to multiple potential pots of money. By far, the largest of those pots is property taxes, but other local sources include a one cent statewide sales tax as a result of Proposition C and other revenue streams. In this section, we will focus on property taxes because, as explained, it dominates the local funding pool of money.

Most Missourians pay property taxes. We pay taxes on real estate we may own—houses, commercial buildings, farms if we have one. We pay taxes on our stuff, including personal property like cars, boats, or farming equipment. Each of those types of properties is assessed at a different rate set by the state, with commercial property assessed higher than residential or agricultural (32% vs. 19% vs. 12%). Every so often, we get a notice that our property taxes are due. Many of us feel better about writing those checks knowing that at least some of the dollars we’re handing over are going to a worthy cause, like education.

Among the taxing authorities who set their taxing rates each October are school districts; libraries; and ambulance, fire, and light districts. Those rates are subject to ceilings or maximums set by state law that allow for cost of living adjustments or increases approved by voters. These rates are applied to the assessed value of a person’s property. For example, a home worth $100,000 has an assessed value of $19,000 (19% for residential properties). If that home is in a district with a 5.0% tax rate for residential properties, then the homeowner would owe $5.00 for every $100 of assessed value, or $950, that would be earmarked for their school district.

While school districts have some discretion over the rate they set every fall, if they want to raise it above a certain point, they have to get voter approval. Chances are you’ve heard of, maybe even voted on, various measures to raise more funding for education. Occasionally these measures are statewide, but usually they take the form of local ballot measures to allow the district to raise its property tax rate or to issue a bond that allows a district to borrow money for certain large purchases (e.g., purchasing land, constructing new buildings, etc.) Maplewood Richmond Heights,40 Brentwood, Webster Groves, Francis Howell, and Wentzville school districts all successfully passed bond issues recently. Tax levies are less common, though Wentzville, Maplewood Richmond Heights and Webster Groves are among the districts that have passed tax increases in the past 10 years.

How effective those tax increases are depends, of course, on the value of the property being taxed. Here we run into at least two issues that greatly impede equitable local fundraising capacity. First, because of a long history of policymaking designed to concentrate wealth and whiteness (discussed in Section 7), some parts of our region have experienced decades of disinvestment and, as a result, their property values have stagnated or fallen. We’ve all heard of the Delmar Divide, where palatial homes on the south side of the street gaze upon poverty to the north. Second, some school districts benefit from higher numbers of profitable businesses who pay higher taxes (business property is taxed at the highest rate—32% compared to 19% for residential property).

What We Looked At

Note: Each of the following indicators were examined by district as well as for majority White and majority Black districts. These classifications were made using 2018-2019 enrollment data from the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (MO DESE).

What We Found

There Is a Strong, Positive Relationship Between Property Wealth and State + Local Education Funding Even Though There Shouldn’t Be

Directly funding education through property taxes without any meaningful redistribution is inequitable. This is not a statement of opinion; it is a statement of fact. The Foundation Formula was developed with the stated aim of correcting for this fact. But there’s what policymakers said they wanted the Formula to do and then there’s what they actually built it to do, and those things are very different. As we asserted in the previous section, in so many ways (e.g., hold harmless provisions, treatment of high-need student populations, the way the formula determines the cost of education, etc.) the Foundation Formula is doing exactly what it was structured to do: give White wealthy districts an unneeded boost.

We can see that same trend from a new vantage point if we look at the relationship between the value of all the property within a district’s boundaries (as measured in its “assessed valuation per student”) compared to the district’s local and state revenue per student. If the Foundation Formula was working to ensure adequacy, we would expect to see a negative relationship between these two variables: districts with lower property wealth would get more funding because their students are more likely to be costly to educate.

Short of this, we might expect to see essentially no relationship between assessed value and local + state funding, which would suggest that, holding the extra costs of educating low income students aside, state funding was bringing poorer districts up to parity with wealthier districts. In practice, we see neither of these things. Instead, we see the opposite of what we should see if equity was centered: there is a strong positive relationship between property wealth and state + local funding for education.

Districts with more wealth to draw on put more dollars into their classrooms. Again, this is partly because the Foundation Formula was poorly built to execute on its theoretical mission. Another part of it, though, is that there is vast variability in wealth from district-to-district, and state funding can’t smooth that out because there simply isn’t enough of it.

Majority White Districts Have Much Greater Residential and Commercial Property Wealth

The median assessed property value for majority Black districts is $97,751 per student. For majority White districts, it’s almost two times higher, at $181,899. The majority White school district with the greatest property wealth (Clayton at $428,446/student) has $173,117 more in assessed property value per student than the majority Black school district with the greatest property wealth (U City at $255,329/student).

The greater property wealth in majority White districts is driven primarily by both residential and commercial properties that are worth more. For example, the median home in majority White districts is worth $215,700, while in majority Black districts it’s worth $91,400. We weren’t able to find data on commercial wealth for all the districts we studied, but we were able to find some, mostly through the notices, like this one from Rockwood in 2019, that districts have to put out before levying taxes. We wondered how commercial property values fit into the overall local funding pie from one district to another. Keep in mind that commercial property is assessed at 32% compared to 19% for residential property, so, we reasoned, districts with vigorous business presences have a sizable advantage over districts that do not.

Let’s look at the example of Brentwood compared to Riverview Gardens.

Tucked in North County, beleaguered Riverview Gardens covers an area of 9.3 square miles. Brentwood, one of the four school districts in the city of Richmond Heights, is smaller, at 2.1 square miles. However, Brentwood punches above its weight when it comes to business activity. Trader Joes, Target, Whole Foods, Dierbergs, Best Buy, and many others can all be found within a quarter mile radius of one another. Anyone who has been to the Target in the Promenade at Brentwood on a Saturday knows all too well just how busy that shopping area is.

That’s a big part of why, in 2018, nearly 35% ($110,588,460) of Brentwood’s assessed valuation of $317,262,750 came from commercial property. By contrast, 13.6% ($26,812,490) of Riverview Gardens’ $198,924,110 of assessed value came from commercial property. The assessed value of the commercial property in Brentwood is more than four times higher than in Riverview Gardens, even though Riverview Gardens is nearly five times bigger in geographic size.

The kicker is this: in 2018, Riverview Gardens enrolled 5,310 students. That same year, Brentwood enrolled 784 students. The massive commercial property wealth represented by all those stores is funneled into education benefits for less than 800 students, most of them White and upper-middle class. Put another way, Brentwood had $141,056 of assessed commercial property value per student, over 28 times more than the $5,049 per student in Riverview Gardens. A similar pattern plays out in Clayton, which is home to the Galleria; Kirkwood (West County mall); and many other majority White districts that benefit from thriving businesses that people come from all over the region to use.

Right about now would be a good time to start reflecting (if you weren’t already) on why those thriving businesses are where they are, what was there before them, and why there are so many fewer such businesses in low-income majority Black districts. We’ll circle back around to that in Section 7.

Majority Black Districts Tend to Pay Higher Taxes

The greater property wealth in many majority White school districts means they can raise enough money without taxing themselves as much as property-poorer districts. To raise the maximum property tax they can levy (i.e., the “tax rate ceiling”) above a certain point, districts need voter approval. Majority Black districts tend to have higher tax ceilings ($4.7804 per $100 of assessed value vs. $4.2732) meaning their residents voted to tax themselves more heavily, despite having about half the income on average. Majority Black districts are also, on average, closer to hitting their tax ceilings. And again, since incomes in these districts are lower, paying these amounts in taxes hurts more. But at the end of the day, even if they tax themselves more, the property in majority Black districts just isn’t worth enough to even come close to the revenues generated in wealthier, Whiter districts.

Consider this final thought experiment: with a 4.4632% school district tax rate, the median household in Kirkwood pays about $2,900, or about 2.9% of their income, in taxes to their school district. For the median household in Jennings to pay a similar amount, the district would have to bump its tax rate up from 5.3889%—already one of the highest in the region—to over 22%, which works out to 9.1% of median household income. It’s just not feasible (it’s also not allowed by state law). And the state Foundation Formula wasn’t built to adequately correct for that fact.

Resources for learning more about these topics

- FundEd: State Policy Analysis. 2020. By EdBuild.

- Budget Basics: K-12 Education. 2017. By Missouri Budget Project.

- Missouri. 2020. By the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

- Real Estate Assessment and Property Taxation. 2011. By David Stokes, Christine Harbin, and Josh Smith of The Show-Me Institute.

Why America’s Schools Have a Money Problem. 2016. By NPR.