Structural Inequity

SEGREGATION

Bottom Line Up Front

Federal, State, and Local Policies and Practices Led to De Jure and Then De Facto Segregation in Our Region and Schools

Download This Section

Download the Funding section of the report

Download Entire Report

Download the entire report

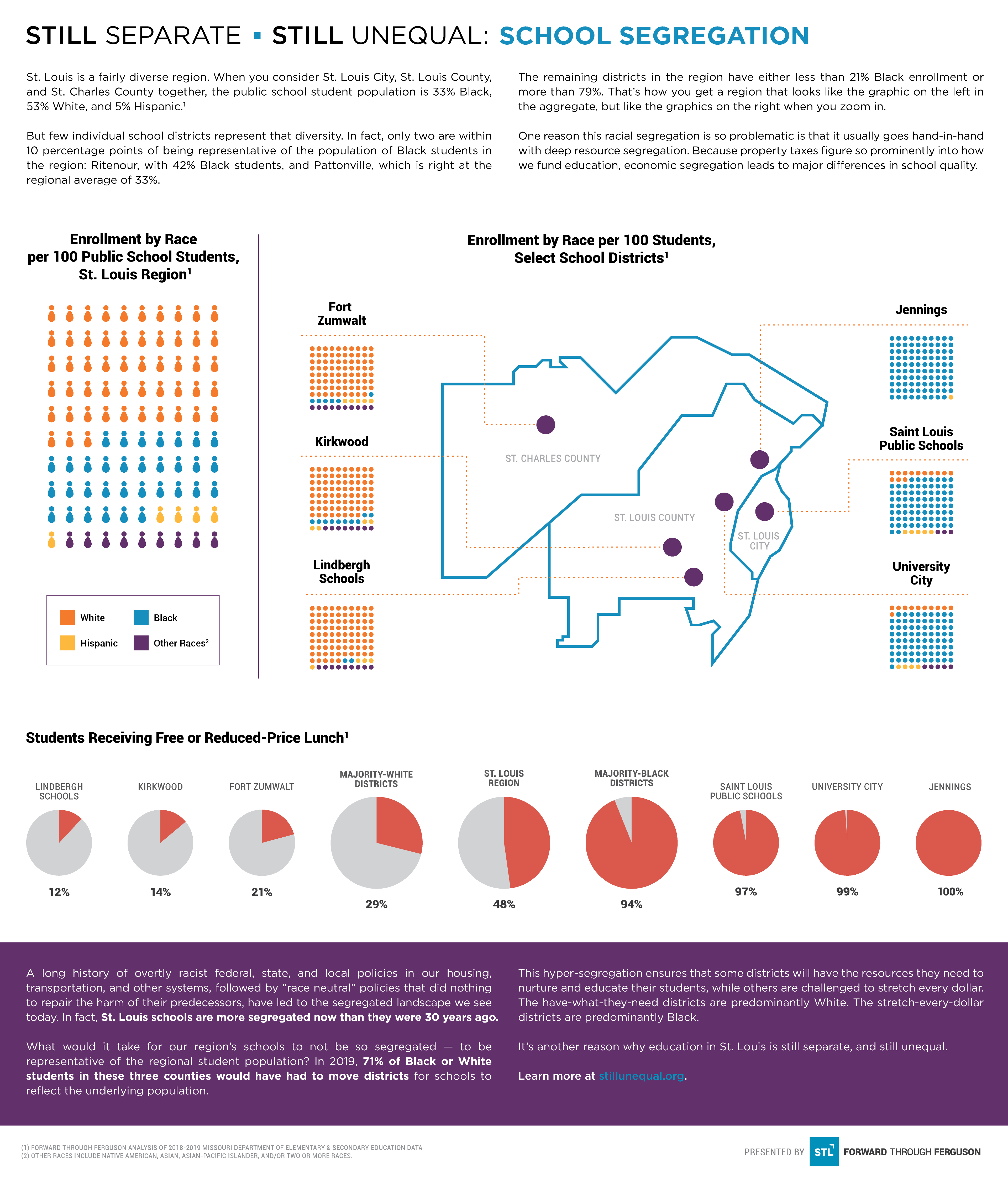

Background (in Brief): A long history of overtly racist federal, state, and local policies in our housing, transportation, and other systems followed by race neutral policies that did nothing to correct for the inequalities of their predecessors have created the landscape of inequality that we see today are primary drivers of district district wealth disparities.

Findings Snapshot:

- For the most part, St. Louis schools have grown more segregated over the past thirty years.

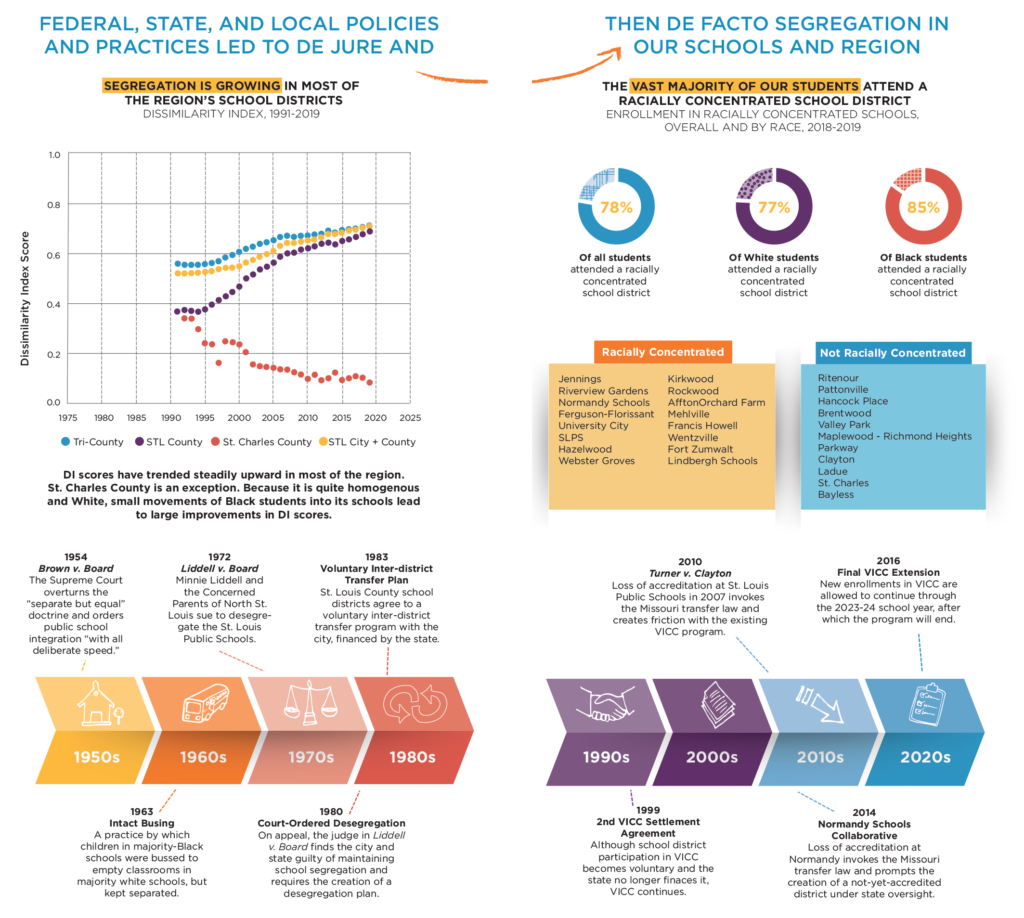

- Dissimilarity Index (DI; a common measure of segregation) scores for our region’s school districts largely stayed level during the 90s. However, as the VICC desegregation program waned, in large part because of the ending in 1999 of the official 1983 order, schools started slipping back towards re-segregation and DI scores increased.

- In 2019, the tri-county (St. Louis City, County, and St. Charles County) public school district dissimilarity index score was 0.71, meaning 71% of Black or White students would have had to move districts for schools to reflect the underlying population.

- Today, our region’s schools are almost as segregated as the nation’s schools were before meaningful integration took place. By comparison, in 1968, soon after Brown v. Board ruled segregated schools unconstitutional, but before most districts had moved to integrate, the dissimilarity index nationwide was about 0.80.

- As a result of de facto (i.e., not legally mandated) segregation, 78% of public school students in the St. Louis region attend a racially concentrated school district, where the vast majority (75% or more) of enrollment is of one race. Even more Black students (85%) attend a racially concentrated school.

Selected Next Steps

(*** indicates a near-term area of focus for FTF)

***Grow broad community understanding of the structural inequities in St. Louis education including the historical and modern-day drivers of educational segregation from the individual up to the systemic level and cultivate an understanding of the approaches available at each level for facilitating integration, and capacity for directly or indirectly implementing those approaches.

“Segregation is embedded in our culture in St. Louis and we subtly do these things we all know like by asking people, “What high school did you go to?” The response automatically gives this image of the person based on where they went and their perceived intellect, income, and knowledge of things. It’s such a part of who we are.”

Click here to read the full conversation between Terry Harris and Dave Leipholtz.

Background

As we saw in Section 6, our education landscape is deeply divided along racial and socioeconomic lines, with majority Black districts having access to a fraction of the property wealth found in majority White districts, especially districts in mid-County and West County. Why is that? What led to these patterns of concentrated wealth and Whiteness and vice-versa? In some ways, the answer is as simple as this: federal, state, and local policies made it exceedingly difficult for Black families to obtain property, and, when they did, if that property became too valuable, local forces used their authority and power to take it. Ultimately, the wild unevenness in wealth and (as we’ll see in section 8) quality in our school districts is rooted in a history of racism and public policy, and, as a result, economic decline.

Housing Policy, Nationally and Locally, Has a Long History of Racism…

For as long as Black individuals have had the right to own land, there have been limitations and conditions constraining that freedom to suit the preferences of White lawmakers and property owners. For a period, namely during the era of the New Deal, many federal, state, and local housing policies were explicitly racist. One of the starkest examples of this is the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934. The FHA is the primary way in which the federal government catalyzes home ownership. It is credited with suburbanizing America and helping to build the (White) middle class. However, for decades, it worked explicitly on the behalf of White Americans: Black homebuyers were not eligible for FHA-backed loans or received far less favorable terms.

Arguing that Black home ownership in or even near burgeoning suburbs would drive down the property values of the White-owned homes they were insuring, the FHA drew maps of metropolitan areas in the country color-coding Black neighborhoods red to indicate that they were too risky to insure. It demanded developers build walls to keep Black individuals from crossing over into White neighborhoods. It insisted on the inclusion of restrictive covenants in the deeds for the properties they insured to guarantee that the homes would never be sold to Black individuals. The policies implemented at a national level by the FHA and other bodies set the tone for state and local policies that nurtured the racist beliefs held by countless individuals.

As historian Colin Gordon points out, St. Louis was, in fact, a national leader in segregationist innovation. In the early 1900s, St. Louis was one of a few cities to formalize racial segregation with the so-called St. Louis Law. The boilerplate language used by the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange in their contracts outlining who could own the properties they sold included “a restriction against selling, conveying, leasing, or renting to a negro or negroes, or the delivery of possession, to or permitting to be occupied by a negro or negroes of said property.” Such restrictive covenants were found unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1948 because of the St. Louis case, Shelley v. Kraemer. But the segregation they created was sustained by private discrimination in real estate and lending, and by public policies such as local land-use zoning.

The homes and neighborhoods the FHA helped develop went on to be the primary vehicle to the middle class for their owners and their families. Affordably priced at twice the median national income in 1950, today they are worth six to eight times the national median income. That increase in equity sent kids to college. It sheltered owners from financial storms as they aged. It served as a springboard for the next generation’s ambitions. These were advantages that were uniquely—and intentionally—afforded to White homeowners. They are major drivers of why, today, Black wealth is one tenth the size of White wealth.

…The Interstate System Has a Long History of Racism, Too

Highways, the FHA urged in its Underwriting Manual, were a great way of separating Black neighborhoods from White neighborhoods. The interstate highway system was created in the 1950s and 1960s. While the federal government took on most of the costs, local officials were often able to influence the paths. In metropolises across the country, those expressways, highways, and interstates were frequently pointed right through “blighted”, majority Black, low-income neighborhoods, displacing millions. St. Louis was no exception. To build Interstate 55, the Black neighborhood of Pleasant View was razed. Interstate 44 pushed Black families out of The Hill and demolished parts of Meacham Park, an established Black neighborhood in Kirkwood.

Let’s Go Back to Brentwood For a Second

Those transportation thoroughfares also shunted economic activity towards some areas, away from others, and directly through still others. Remember the Brentwood School District, home to just under 800 mostly White, wealthy students? It wasn’t always that way. At the intersection of Eager Road and Brentwood Boulevard, where you now will find a bustling commercial hub, was once the Black neighborhood of Howard-Evans Place. Established in 1907, Howard-Evans Place predated the Great Migration and was home to the workers of the Evens & Howard Fire Brick Co and their families. Recalled as one of the first places a Black family could buy a new home in St. Louis. It went on to become a bastion of the Black middle class. By the 1970s, because of its prime location, Howard-Evans Place had captured the attention of others. Highway expansion, redevelopment plans, and Metrolink expansion all threatened the neighborhood multiple times starting in 1977. Finally, in 1995, the neighborhood association agreed to a buyout, leading to the development of Brentwood Promenade.

When the buyout took place, the City of Brentwood valued the property of Howard-Evans Place at $3.6 million. After Brentwood Promenade was developed, it was valued at $30 million. The Promenade also encouraged an additional $300 million in development in Brentwood over the next five years, including the redevelopment of Brentwood Square Town Center, Brentwood Pointe, and the Villas at Brentwood. Today, the economic benefits of that thriving retail center are enjoyed almost solely by the small and affluent Brentwood school district.

A similar pattern of Black displacement to allow for development that disproportionately benefits White St. Louisans has been repeated throughout the region, from Clayton, to Mill Creek Valley, to Meacham Park.

Schools Both Contribute to and Are Impacted By Segregation

Schools were part and parcel of the overt and implicit ways in which racial lines were drawn in our region; indeed, they were among the last of our institutions to desegregate. While Brown v. Board found segregated schools to be unconstitutional in 1954, it took decades for desegregation to actually happen. This led to a second ruling by the Supreme Court in 1955, often called Brown II, that ordered states to integrate with “all deliberate speed,” which in practice was vague enough to allow segregationist states to delay. Missouri dragged its feet until it removed the language from its constitution in 1976—22 years after Brown v. Board of Education and longer than most states in the south. (If you’re wondering, some states, like Alabama, still officially require racially segregated public education under state law). While the Supreme Court decision invalidated these portions of state constitutions, their continued existence long after the nationwide order banning segregation points to an unwillingness to let go of formalized structures for excluding Black students. Meaningful desegregation in St. Louis only occurred years later in 1983 with the implementation of an interdistrict transfer program, over a decade after a court decision on the pivotal 1972 case of Liddell v. Board of Education of City of St. Louis.

The suit argued that Black students enrolled in SLPS received a lower quality education. While school boundary lines were constantly being redrawn, they always kept Black children in Black schools and segregated classrooms. The case moved through the court system for the next two decades. In 1980, the judge overseeing the case proposed a voluntary exchange program between City and County districts. This required the support of county school districts, which many only gave when the overseeing judge threatened to consolidate City and County school districts. In 1983, a voluntary agreement was reached and approved by all 23 districts—though notably North County majority-Black districts were excluded from the exchange program—and was implemented by the Voluntary Interdistrict Coordinating Council (VICC). Pushback from the state on its culpability and financial responsibility extended the case for another decade, and, while the VICC program was up and running throughout that time, it wasn’t until 1993 that all parties in the lawsuit came to an agreement. Around the same time, the Supreme Court handed down its verdict on Missouri v. Jenkins, which invalidated the interdistrict desegregation strategy in Kansas City. Fearing that the state of Missouri would finally get its way and end the VICC program through the courts, the parties from the Liddell case agreed to a second settlement agreement. The VICC program was cemented through 2008-09 (and renewed in 2007, 2012, and 2016, for likely the last time) and became the largest and longest running desegregation program in the country. The magnet school program was also born out of the agreement.

The backdrop to the Liddell case was the 1974 Supreme Court case Milliken v. Bradley, which is credited for allowing schools to remain segregated when it found that segregation was allowed if it was not explicitly stated in policy.

“Race Neutral” is Not Neutral

In the wake of the Civil Rights Act and other landmark legislation like the Fair Housing Act and jurisprudence like Brown v. Board of Education, we have seen a shift away from overtly (de jure) racist policy. But striking down those policies did not undo the damage they did–the inequalities they planted. Left untreated, those inequalities have flourished, fertilized by the benign neglect and passive acceptance of current day “race neutral” policies. As a result, the patterns we see in health, wealth, and well-being in the St. Louis region bear a haunting resemblance to the redlining maps of decades ago.

What We Looked At

More About the Dissimilarity Index

Segregation can be measured in several ways. In fact, the concept of segregation has been broken down into 5 fundamental dimensions: evenness, exposure, concentration, centralization, and clustering. Evenness is probably what most people think of when they define segregation. It refers to the way different sub-populations are physically distributed in a space, be it a city, a state, or a school district. Populations are less segregated when sub-populations are more evenly distributed. The most commonly used indicator of evenness is the Dissimilarity Index (DI). The DI looks at the sub-population makeup of sub-divisions in the overall geography being studied. It measures the percentage of a sub-population that would have to move for each sub-division to have the same population breakdown as the overall geography. The index ranges from 0.0 (perfect integration: the sub-divisions perfectly reflect the diversity of the overall region) to 1.0 (complete segregation: the sub-divisions contain only one sub-population).

For our analyses, we considered counties and the school districts they are made up of. We calculated dissimilarity index values for the public school districts in St. Louis County, St. Charles County; the combination of St. Louis City and St. Louis County; and the tri-county region made up of St. Louis City, St. Louis County, and St. Charles County. Using data from MO DESE, we calculated DI scores for each of these geographies for the years from 1991 to 2019. Because St. Louis City is made up of a single public school district, we could not calculate a Dissimilarity Index score for it alone.

Because we used school districts as the unit of analysis, our DI calculations do not take into account what was happening between schools within a district or outside of the public school system. That means some dynamics we only see indirectly. For example, if a new charter school opened, its numbers would not directly be incorporated into our calculations, but we might be able to observe the effect of that opening because of the students who left the public school system and the decline in enrollments as a result. Other dynamics we are unable to detect at all. For example, students moving from private schools to charters or vice versa wouldn’t be captured in our analyses.

Nonetheless, the DI scores provide an informative snapshot of segregation in our public schools during the peak of the VICC program in the late 90s, the decline of that program in the 2000s, and the triggering of the transfer law in the 2010s (more about this in Section 8).

What We Found

More About the Dissimilarity Index

Segregation can be measured in several ways. In fact, the concept of segregation has been broken down into 5 fundamental dimensions: evenness, exposure, concentration, centralization, and clustering. Evenness is probably what most people think of when they define segregation. It refers to the way different sub-populations are physically distributed in a space, be it a city, a state, or a school district. Populations are less segregated when sub-populations are more evenly distributed. The most commonly used indicator of evenness is the Dissimilarity Index (DI). The DI looks at the sub-population makeup of sub-divisions in the overall geography being studied. It measures the percentage of a sub-population that would have to move for each sub-division to have the same population breakdown as the overall geography. The index ranges from 0.0 (perfect integration: the sub-divisions perfectly reflect the diversity of the overall region) to 1.0 (complete segregation: the sub-divisions contain only one sub-population).

For our analyses, we considered counties and the school districts they are made up of. We calculated dissimilarity index values for the public school districts in St. Louis County, St. Charles County; the combination of St. Louis City and St. Louis County; and the tri-county region made up of St. Louis City, St. Louis County, and St. Charles County. Using data from MO DESE, we calculated DI scores for each of these geographies for the years from 1991 to 2019. Because St. Louis City is made up of a single public school district, we could not calculate a Dissimilarity Index score for it alone.

Because we used school districts as the unit of analysis, our DI calculations do not take into account what was happening between schools within a district or outside of the public school system. That means some dynamics we only see indirectly. For example, if a new charter school opened, its numbers would not directly be incorporated into our calculations, but we might be able to observe the effect of that opening because of the students who left the public school system and the decline in enrollments as a result. Other dynamics we are unable to detect at all. For example, students moving from private schools to charters or vice versa wouldn’t be captured in our analyses.

Nonetheless, the DI scores provide an informative snapshot of segregation in our public schools during the peak of the VICC program in the late 90s, the decline of that program in the 2000s, and the triggering of the transfer law in the 2010s (more about this in Section 8).

What We Found

School Districts Generally Grew More Segregated Despite VICC

We pick up this story in the early 1990s in our school districts. As our analysis of Dissimilarity Index (DI) scores shows, for the most part, our schools have grown more segregated over the past thirty years. DI scores measure the percent of the population that would have to move to create (in our case) school districts that reflect the racial diversity of the region. Scores range from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating perfect integration and 1 indicating complete segregation; scores over 0.6 are considered high levels of segregation.

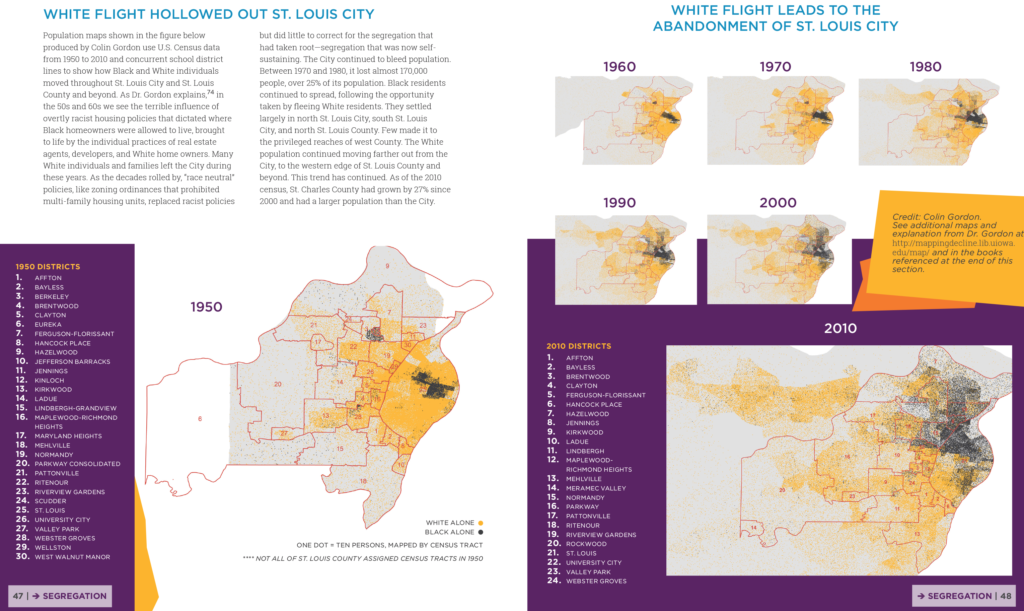

In 1991, the tri-county region (St. Louis City, St. Louis County, and St. Charles County), had a DI score of 0.56. About 1 in 2 Black or White students would have had to change school districts to create a public education landscape that modeled the diversity of the public school students living in those three counties. Reading between the lines, we see that the high levels of segregation for the region overall were driven, in 1991, by racial unevenness in St. Louis City and St. Charles County. The DI score for St. Louis County was actually considerably lower at 0.36, due in large part to a relatively large Black population that was more distributed. That changed, though. In the ensuing years, White students continued to leave St. Louis City. Many kept going through St. Louis County, settling in St. Charles County.

This White flight further segregated schools in St. Louis City and County, driving the DI scores up for this subset of the region. St. Charles County’s school districts were almost entirely White in 1991. In fact, Black enrollments were so low in some districts, like Francis Howell, the largest district in St. Charles, that they could not be counted without compromising privacy. When Francis Howell enrolled 204 Black students in 1992, the DI score for all of St. Charles County dropped from 0.52 to 0.34. Over the past 30 years, St. Charles County’s DI scores have dropped as the County’s Black population slowly grew. Today, there are about 4,200 Black students across all of the public schools in St. Charles County. There are nearly 89,000 Black school-aged children in the region.

We can’t fully celebrate St. Charles County school districts’ low segregation scores because they disguise the fact that most Black students are still segregated away from those districts to begin with. There’s even less to celebrate in St. Louis City and County.

Despite the efforts of the VICC desegregation program, Black and White enrollments in public school districts in the City and County have grown more uneven in the past 30 years. The VICC program began enrolling students in 1983 and, by 1999, it had reached its peak, enrolling 14,000 students. Most of those students were Black, from the City, and using the program to go to school in the County. That program is probably why, until about 2000, dissimilarity index scores remained pretty level in St. Louis City + County. As the VICC program waned, in large part because of the ending in 1999 of the official 1983 order, schools started slipping back towards re-segregation and DI scores increased. The school districts in north St. Louis County were not part of the VICC program and those districts have largely remained intensely segregated.

Schools Are Nearly as Segregated Today as in 1968, Before Deseg

In 2019, the tri-country dissimilarity index score was 0.71 meaning 71% of Black or White students would have had to move districts for schools to reflect the underlying population. As a result of de facto (i.e., not legally mandated) segregation, 78% of public school students attended a racially concentrated school district, where 75% or more of enrollment is of one race. Even more Black students (85%) attended a racially concentrated school. 17 out of the 28 school districts we examined were racially concentrated. By comparison, in 1968, soon after Brown v. Board ruled segregated schools unconstitutional, but before most districts had moved to integrate, the dissimilarity index nationwide was about 0.80. Today, our region’s schools are almost as segregated as the nation’s schools were before meaningful integration took place. And as Brown v. Board unequivocally stated in 1954, “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Resources for learning more about these topics

- Citizen Brown, 2019. By Colin Gordon.

- The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, 2017. By Richard Rothstein.

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America, 2018. By Robert Nelson and colleagues.

Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City, 2009. Colin Gordon.